Lexical scoping and redefining function application

The previous post layed the foundations of creating a language and “compiler” using Racket macros.

This is all very nice, but utimately it is just a bunch of macros. The “language” itself doesn’t have any form of enforced semantics. You can introduce whatever syntax and macros you want, and use them however you like, even if it makes no sense at all.

Whilst this is nice in a way (and can lead to some .. interesting .. “features”) it is often more of a pain than it’s worth. Most of the errors we make in our day to day programming are picked up immediately by the background compiler, or the full compilation. Silly things like “clipboard inheritance” or typos attempting to use bindings that aren’t in scope are high on the list of culprits here.

In this post we will see how Racket can be used to help out by doing some lexical scope “analysis” in a slightly different way from a traditional compiler. We will also see how Racket can redefine its entire notion of function application, which will allow us to introduce some very nifty new syntax into Scurry itself.

Lexical Scoping

Scurry supports local bindings, lambdas and closures. This means that a given section of code can only “see” bindings that are in scope for it. The virtual machine itself of course manages this, but I can tell you it’s not much fun having to compile a program, load it in the VM and run it only to discover that you spelt “john” or “x” wrong.

A traditional compiler will lex/parse the code and produce an asbtract syntax tree. It will then perform a semantic analysis pass where it checks to make sure everything “makes sense”. This includes type checking and lexical scoping, amongst possibly other things. I don’t care about type checking for this language, but it would be nice to make sure bindings that are being used are in scope! Unlike a normal compiler though, the “compilation” here is happening within the racket compiler via macro expansion. This puts us in a unique position where we are “there as it happens” rather than “looking at it afterwards”.

A macro itself can also execute Racket code just like it can at runtime.

1 2 3 4 |

(define-syntax-parser test

[(_)

(writeln "at compile time")

#'(writeln "at runtime")])

|

This means we can do some interesting stuff such as track what is going on during compilation by writing whatever code we want. In this case, we can emulate what the VM does by keeping track of what bindings are in scope. The data structure for this is a stack of sets, where the stack represents layers of scopes and the sets are the names of bindings.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

(begin-for-syntax

(define scoped-bindings-stack (box (list (mutable-set))))

(define (push-scoped-stack)

(let* ([lst (unbox scoped-bindings-stack)]

[new-lst (cons (mutable-set) lst)])

(set-box! scoped-bindings-stack new-lst)))

(define (pop-scoped-stack)

(let* ([lst (unbox scoped-bindings-stack)]

[new-lst (cdr lst)])

(set-box! scoped-bindings-stack new-lst)))

(define (peek-scoped-stack)

(let ([lst (unbox scoped-bindings-stack)])

(car lst)))

(define (add-scoped-binding stx-name stx)

(let ([name (syntax-e stx-name)]

[scoped (peek-scoped-stack)])

(when (set-member? scoped name)

(writeln

(format "warning: ~a is already in scope at ~a"

name (source-location->string stx))))

(set-add! scoped name)))

(define (in-scope? name)

(define (aux lst)

(cond

[(empty? lst) #f]

[(set-member? (car lst) name) #t]

[else (aux (cdr lst))]))

(aux (unbox scoped-bindings-stack))))

|

You’ll notice the first thing is begin-for-syntax this elevates the phase-level by one, which makes this set of bindings accessible from the macros, meaning this stuff will happen at compile time.

You can see I am using mutable sets and (effectively mutable) lists for this implementation. Racket is a functional language and I’m sure there’s nicer ways to do this at compile time, but this is (currently) easy to reason about and it works just fine, so it will do for the time being!

Most of this is not very interesting - it does what you would expect and provides functions for pushing / popping new scopes, adding a binding name to the current scope, and a function that walks up the stack looking for a binding with a particular name.

One part that is interesting is inside add-scoped-binding - you can see it takes a syntax object stx which it can use to present a warning to the user if they have shadowed a binding, along with the location in the source file where it occured.

Let’s introduce a new syntax class like the binding one from the last post, with a key difference.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

(begin-for-syntax

(define-syntax-class scoped-binding

#:description "identifier in scope"

(pattern x:id

#:with name (symbol->string (syntax-e #'x))

#:when (in-scope? (symbol->string (syntax-e #'x))))))

|

This is identical to the other syntax class, except it has a when clause that says the stringified version of it must be in-scope?.

Since all uses of bound identifiers as arguments must at some point or another come through the eval-arg macro, we can make a small tweak from this:

1 2 3 4 5 |

(define-syntax-parser eval-arg

[(_ id:binding)

#''((ldvar id.name))

; rest of macro

|

to this:

1 2 3 4 5 |

(define-syntax-parser eval-arg

[(_ id:scoped-binding)

#''((ldvar id.name))

; rest of macro

|

And that’s it. We will now get compile errors anywhere in the entire language that we try to use an identifier that is not bound. Of course, we are missing a piece, which is modifiying the macros that introduce bindings and scopes to call the relevant functions. Here’s def:

1 2 3 4 5 |

(define-syntax-parser def

[(_ id:binding expr)

(add-scoped-binding #'id.name this-syntax)

#'`(,(eval-arg expr)

(stvar id.name))])

|

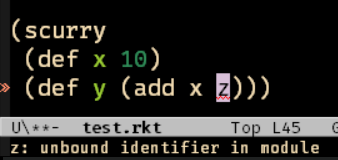

Notice here the background compiler has picked up this error in Emacs! This is because the error occurs at macro expansion time.

Here is lambda:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

(define-syntax-parser s-lambda

[(_ (arg:binding) body)

(push-scoped-stack)

(add-scoped-binding #'arg.name this-syntax)

(with-syntax

([label (new-label)])

#'`(

;tell the assembler to create this later

(pending-function

label

(stvar arg.name)

,body

,(pop-scoped-stack)

(ret))

(lambda label)))])

|

Notice in lambda I am using ,(pop-scoped-stack) which should not work since it’s at a different phase level (since it’s in the syntax being returned). I used a little trick here where I simply define a macro with the same name that it CAN see, that returns an empty list (there’s probably a nicer way to do this, I have not much clue what I am doing yet).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

(define-syntax-parser pop-scoped-stack

[(_ )

(pop-scoped-stack)

#''()])

(define-syntax-parser push-scoped-stack

[(_)

(push-scoped-stack)

#'`()])

|

Regardless, this is quite cool! The actual compiled bytecode of the lambda itself is re-arranged by the assembler much later and put at the bottom of the binary file. The scoping doesn’t care about this though as it only deals with what happens at expansion time. In this case, ,body gets expanded first, then the scope is popped during expansion of ,(pop-scoped-stack), which means in the source definition of the lambda you will only have access to things bound lexically above you :)

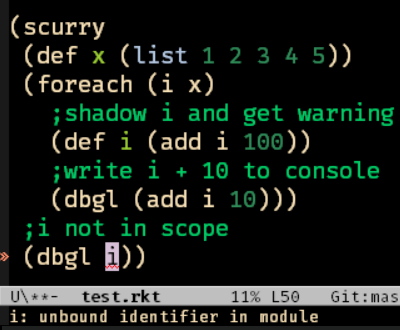

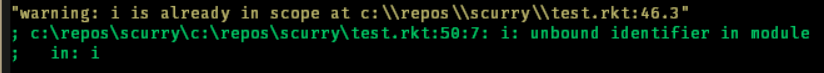

Of course this is not limited to lambdas, it means now you can create macros that suggest scope, and have it enforced for you by the compiler. For example, Scurry is part functional part imperative, so it follows one of the most-used tools is foreach which allows you to bind each element of a list to some identifier and then use it in the body. I have now placed the scoping functions at the relavent places and the compiler will stop you attempting to use the bound identifier outside of the foreach scope.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

(define-syntax (foreach stx)

(syntax-parse stx

[(_ (var:binding list-expr) exprs ...)

(with-syntax*

([label (new-label)]

[continue (new-label)]

[idx (new-var)]

[start

#'`(

,(eval-arg list-expr)

;test there are items otherwise skip

(p_len)

(ldval 0)

(beq continue)

(ldval 0)

(stvar idx)

(label ldvar idx)

(p_index)

(stvar var.name))]

[end

#'`(

(p_len)

(ldvar idx)

(inc)

(p_stvar idx)

(bne label)

(continue)

(pop)

,(pop-scoped-stack))])

(push-scoped-stack)

(add-scoped-binding #'var.name stx)

#'(start exprs ... end))]))

|

Here is an example of using foreach, where we shadow the binding i and get a warning for it, then try to use it again outside of the scope and get an error.

Property Accessors

The core datatype in Scurry, much like JavaScript or Lua, is a string->object dictionary.

1 2 |

(def-obj player (["name" "juan"]

["coins" 0]))

|

In order to use a property you must use the somewhat verbose get-prop syntax

1 |

(def money (get-prop player "coins"))

|

This is very flexible as you can determine the object and the key with expressions, however, a lot of the time you just want to pass a property to some function call. As you can imagine, this can quickly get annoying. Even worse, if you want to add 10 to the player’s money, you’d have to do this

1 |

(set-prop player "coins" (add (get-prop player "coins") 10))

|

Nasty! Since this is so common, I wrote some macros so you can do the following

1 |

(prop+= player "coins" 10)

|

Better, but still not very satisfing.

What I would really like is a sytax like Lua where i can write obj.prop as shorthand to refer to a property. Let’s see if we can write a syntax class to help do exactly that

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

(begin-for-syntax

(define-syntax-class prop-accessor

#:description "property accessor"

(pattern x:id

#:when (string-contains? (symbol->string (syntax-e #'x)) ".")

#:with ident (car (string-split (symbol->string (syntax-e #'x)) "."))

#:when (in-scope? (syntax-e #'ident))

#:with prop (cadr (string-split (symbol->string (syntax-e #'x)) "."))

)))

|

Here we check if the bidning has a "." in it and then split it into two halves. We also check the left half is in-scope? whilst we are at it, and return the left and right sides as ident and prop.

(apologies for the redundant bits of code here, I’ve not worked out how to sort that out yet!)

Now we can add a new ’lil case to the old faithful eval-arg macro:

1 2 |

[(_ id:prop-accessor)

#'(get-prop id.ident id.prop)]

|

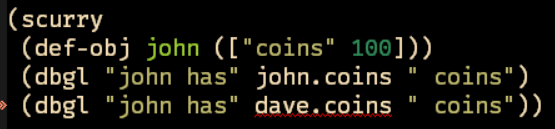

And we are done. Now, we can use the shorthand property acessor anywhere in the whole language that accepts an argument! As an extra bonus, it will give you a compile error if you get your identifier wrong.

Fantastic! What about the other problem though? Wouldn’t it be really nice if you could write this, in completely non-lisp style?

1 2 |

(john.coins += 10)

(john.coins = 58)

|

Of course, Lisp generally only accepts the prefix style, where the first element in the list must be a macro or function name. This would mean that join.coins would have to be a macro or function - that would be silly though, obviously!

One of the coolest tools in the Racket toolbox is the ability to override the way it applies functions themselves. It gives you the ability to “get in there first” and match on the whole pice of syntax and re-arrange it before it carries on (if it has not already matched the name to a macro, as far as I understand). There is a little logistical work to enable this which I won’t cover here, but essentially you end up re-defining the special form #%app

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

(define-syntax (app stx)

(syntax-parse stx

#:datum-literals (= += -=)

[(app f:prop-accessor += val)

#'(prop+= f.ident f.prop val)]

[(app f:prop-accessor -= val)

#'(prop-= f.ident f.prop val)]

[(app f:prop-accessor = val)

#'(set-prop f.ident f.prop val)]

; process everything else as normal

[(app f . a) #'(f . a)]))

|

In this very cool piece of code, we pattern match on the syntax just like any other macro, except this time we are matching on all applications. You can see here I use the prop-accessor syntax class in the head position, followed by one of the three literals = += and -=. If these match, they are rewritten to their relevant scurry forms, otherwise, we allow the application to carry on as it normally would.

Now, this code works, and we still get the in-scope check :)

1 2 3 4 5 |

(scurry

(def-obj john (["coins" 100]))

(dbgl "john has" john.coins " coins")

(john.coins += 10)

(dbgl "john now has" john.coins " coins"))

|

Imagine the possibilies with this!

In fact, here’s a very cool one. Since Scurry is a mixture of compile time macros and lambda function applications, I had to have a macro to perform the function application:

1 2 3 4 |

(define-syntax-parser ~

[(_ f args ...)

#'`(,(eval-arg f)

((,(eval-arg args) (apply)) ...))])

|

This is great, but it gets very annoying having to write (~ f arg) everywhere, and it’s easy to forget. Wouldn’t it be nice if Racket just assumed everyhing that wasn’t a macro must need a scurry function application?

1 2 |

; process everything else as a scurry function appication

[(app f . a) #'(~ f . a)]

|

Done! Now the entire language no longer needs explicit function application.

That’s it for this time around, I hope this shows you some more of what Racket is capable of.